As Latino population grows, so does push for place at California universities

When the University of California, Santa Barbara, announced last month that it had been named a Hispanic-Serving Institution, it made a small bit of history.

After a decades-long effort to boost enrollment from underserved communities, the Isla Vista campus became the first member of the elite Association of American Universities, an organization of 62 leading research universities, to reach the HSI designation.

Awarded by the federal government, the status signifies that at least 25 percent of the school’s student body is Latino, making it eligible for new programs and millions of dollars in targeted grants. It also indicates that the work of California’s public university systems to reflect the state’s increasing diversity is paying off.

“It basically says that a top-ranking, national university can be a diverse campus and that adds to its strength,” said Lisa Przekop, director of admissions for UC Santa Barbara. “It sends the word out nationally.”

Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Institution marks a major shift for UC Santa Barbara, long known for its surfers and parties. Przekop remembers her own “panicked feeling” as one of the few Mexican American students when she arrived on campus in 1982.

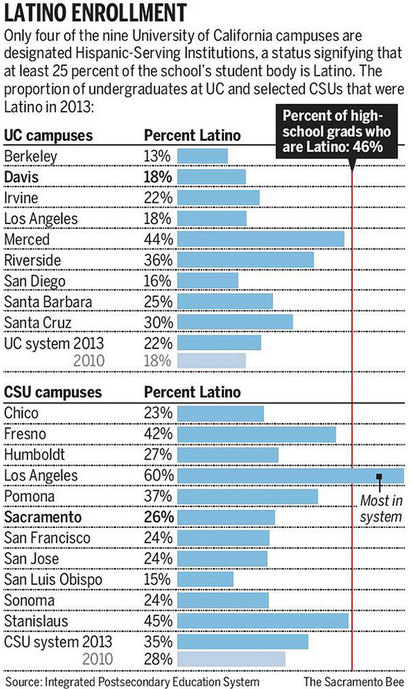

But Latinos remain vastly underrepresented at the University of California, where four of nine campuses have been designated HSIs, and California State University, where 18 of 23 campuses and the system as a whole have reached the benchmark. While they now comprise more than 46 percent of California high school graduates, only about 22 percent of undergraduates at UC and 35 percent at CSU are Latino.

Advocates argue that the universities must do more to reach the swelling ranks of California’s Latino student population, as a matter of both equity and economics.

“It’s kind of like a rooster taking credit for the sunrise,” said Michele Siqueiros, executive director of the Campaign for College Opportunity. “You can’t sustain the strength of California’s economy if you don’t do a better job of educating our population.”

Expanding the diversity in their student ranks has been a goal for UC and CSU for years.

While acknowledging that the state’s shifting demographics have driven much of the changes in the student body, UC Santa Barbara officials also pointed to numerous outreach efforts: visits to rural high schools and those that have not traditionally submitted many applications, bus tours to the campus, resource guides for ethnic groups, and educational tools for counselors to ensure students fulfill eligibility requirements.

Initiatives are also taking place at the systemwide level. CSU conducts Spanish-language college fairs and parent training programs in the communities near its campuses, sponsors Latino-oriented academic conferences, and produces a bilingual insert about college preparation in the newspaper La Opinión.

UC Davis, where about 19 percent of undergraduates are Latino, recently committed to reaching the Hispanic-Serving Institution benchmark by 2018. It has stepped up recruitment and transfer agreements at community colleges, while working with Latino students as young as kindergarten to get them excited about the possibilities of college.

Sacramento State is just on the cusp of 25 percent and expects to be designated within the year. President Alexander Gonzalez, who previously led Latino enrollment pushes at CSUs in Fresno and San Marcos, is looking forward to seeing a large, destination campus like Sacramento achieve that level of diversity. “For us,” he said, “it’s going to be a real milestone.”

Schools with HSI status can see significant benefits. Federal agencies ranging from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to the National Endowment for the Humanities have awards aimed at Hispanic-Serving Institutions, and $98 million in funding was available through the U.S. Department of Education last year, according to the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities, an advocacy group for HSIs.

UC Riverside, which is more than 32 percent Latino, was the first UC campus to be designated, in 2008. Steve Brint, vice provost for undergraduate education, said the university has subsequently been able to attract funding to expand its undergraduate research opportunities and create new student support programs, such as a fellowship for minorities interested in careers in academia.

A $4 million grant from 2008 to 2011, funded by the federal College Cost Reduction and Access Act, supported a project with regional community colleges to ensure science, technology, engineering and mathematics students were well-prepared to transfer to UC Riverside.

Brint added that the HSI status has also helped the campus build good ties with its community and recruit more Latino students.

“We have critical mass of all groups, so students feel quite comfortable,” he said. “They feel it’s a welcoming campus and an inclusive campus.”

Carl Gutiérrez-Jones, the acting dean of undergraduate education at UC Santa Barbara, said the school will now be pursuing grants for programs to help students transition to campus, complete their degrees on time, cut down on attrition and prepare for graduate study.

“The focus is on the Hispanic students, but once those awards arrive, they benefit all students,” he said.

He also hopes the HSI designation will help UC Santa Barbara shake lingering stereotypes.

“If students come to an institution where they feel they belong, their ability to persist and overcome challenges is really assisted,” Gutiérrez-Jones said. “That success feeds on itself.”

Siqueiros is glad to see Latino enrollment increasing, but she won’t be excited until it is proportional to high school graduation in California.

“We’re never going to reach that level, because there’s never going to be enough resources to ensure that information is getting to every student,” she said. “If you don’t change the structure, then you’re not going to have a different result.”

She said California should reconsider the admissions practices of its public universities – whether they turn away too many qualified applicants with their guaranteed admissions cutoffs (the top 9 percent of high school graduates at UC, the top one-third at CSU); whether the academic eligibility requirements are adequate when many high schools don’t see college preparation as part of their role; and whether race should still be banned as a factor in admissions decisions.

A legislative effort to overturn that racial ban by placing a ballot measure before voters stalled last year when Asian American lawmakers, under pressure from constituents, joined Republicans in opposition.

“Colleges could be much more proactive and engaged,” Siqueiros said.

For now, they’re still sorting through the responsibilities of serving California’s rapidly growing Latino student population.

Members of the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities will meet this year to discuss their mission as HSIs, according to association chair and CSU San Bernardino President Tomás Morales. He suggested the universities should focus on raising Latinos’ degree attainment and work more to improve their surrounding, often heavily Latino, communities.

“What does it really mean to be a Hispanic-Serving Institution, beyond simply the numerical designation?” he said. “That’s a hard question to answer.”