UC’s $15 minimum wage leaves out many workers

By Chris Kirkham

Michael Del Rio has worked for nearly three years as a custodian at UC San Diego’s Thornton Hospital, reporting to the same bosses, working with the same colleagues and cleaning the same facilities.

But he has led two lives. At first Del Rio worked for HireCare, a UC San Diego subcontractor. He earned $13.75 an hour with no benefits, and he had to work holidays and weekends — missing out on one of his son’s birthday parties.

When the UC system hired him directly last year, his pay shot up to $15.83 with guaranteed annual raises. He has full health coverage and retirement benefits, providing the stability for his wife to now attend college full time.

As for the work: “The only thing that changed was the uniform,” he said.

Del Rio considers himself lucky. Like many of the nation’s largest employers, the University of California system relies on a vast network of subcontracted and temporary employees to fuel its daily operations — custodial work, landscaping, food preparation, security services. Many work the same shifts for years, with little in the way of job security, earning close to the minimum wage.

When the UC system announced plans to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2017 for both direct and contract employees, it rekindled a long-standing debate about working conditions at one of the world’s most prestigious learning institutions — California’s third-largest employer.

UC officials said the vast majority of its direct employees already make well above $15 an hour. The university estimates only about 1.6% of its 201,000 direct employees across the state will get a raise.

They have no estimates on how many subcontracted employees make less than $15 an hour — or how long it will take for the raises to eventually kick in. That’s because contracts are spread out across 10 campuses, five medical centers and many other research facilities. They include short-term construction projects and long-range agreements for cleaning athletic facilities and attending parking garages.

————

FOR THE RECORD

Aug. 12, 12:30 p.m.: An earlier version of this article incorrectly said there are nine UC campuses. There are 10.

————

“There’s no real way of giving an exact number, or anything beyond an estimate,” said UC spokeswoman Dianne Klein, who said the number of subcontractors is surely “thousands more.”

The rise of the so-called contingent workforce in the U.S. — subcontracted workers, temps, independent contractors — has gotten increased attention from labor economists in recent years, as companies including Uber, Wal-Mart and Amazon have relied more on outsourced workers. Large public institutions such as UC have done the same.

Many experts have pointed to the outsourcing of work — particularly in low-wage service industries — as a contributor to lower standards of living.

A study this year from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that contingent workers, including subcontractors, earned an average of 16.7% less each week than standard employees. Such work arrangements typically lead to “lower earnings, fewer benefits and a greater reliance on public assistance,” the report concluded.

Policymakers have increasingly focused on how public institutions can shape labor standards across the economy. A U.S. Senate report from 2013 found that nearly 30% of the top violators of federal wage and safety laws were also federal contractors.

The Obama administration has since increased the minimum wage to $10.10 for federal construction and service contractors, and ramped up scrutiny of contractors that violate labor laws.

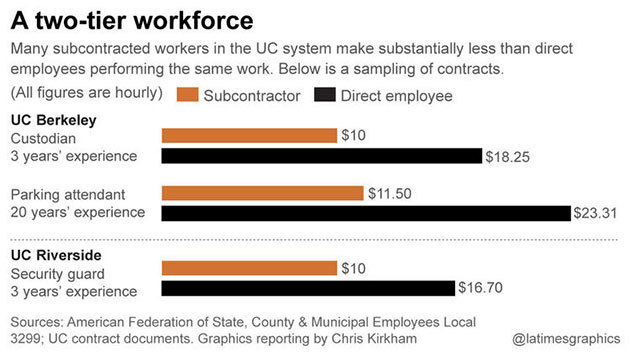

In California, labor advocates for years have targeted the UC system’s reliance on subcontractors, pointing to the disparities between outsourced workers earning near the minimum wage and unionized full-time workers who do the same jobs and can make more than twice as much.

UC’s chapter of the American Federation of State, County & Municipal Employees union released a report Friday arguing that the university’s two-tier workforce model is “eliminating middle-class career pathways, and adding to the ranks of California’s working poor.” Drawing on public records requests, the report identified at least 45 contracts across the system in which subcontracted employees performed the same tasks as career UC workers.

The group could not conclude whether UC’s contracting had increased in recent years. But the report found that the number of full-time service employees across the UC system fell by about 150 from 2009 to 2014, even as the number of full-time students increased by nearly 9,000. UC says the worker tally rose by one over that period.

UC is “a huge economic engine,” said Kathryn Lybarger, president of UC’s AFSCME chapter, who also works as a lead gardener at UC Berkeley. “Their policies and their employment practices have an impact on the economy, and more broadly they have an impact on the communities where these campuses are anchored.”

Klein, the UC spokeswoman, said the university system has recognized those criticisms and responded with the $15 minimum wage plan. That process will take time, however, because the university cannot change the terms of existing contracts until they expire.

Klein said that as new contracts come online, UC will be doing unannounced inspections to ensure contractors are following the new wage rules, and has set up a hotline for workers to report violations.

“If you want the work as a contractor, we’re saying you can’t cut costs on the backs of the workers,” Klein said. But she said the university disagrees with the union’s position that all contract workers should be brought on as full-time employees with benefits and retirement.

“The university needs to remain nimble and able to retain contractors as appropriate,” she said. “We do not feel that it’s beneficial or cost-effective to have everyone on as a full-time UC employee. It limits our flexibility.”

The state Senate recently passed a bill that would require UC contractors to provide wages and benefits equal to direct employees. UC opposes the legislation, which is pending in the Assembly, saying it would increase costs by $66 million and “create new administrative burdens.”

Contract workers say the benefits are just as important as the pay. For two years Consuelo Barrera has worked full time for Performance First Building Services, a custodial contractor at UC Berkeley, cleaning up after sporting events.

She makes $10 an hour, $1 above the state minimum, and said an eventual boost to $15 still won’t enable her to afford costly health insurance premiums offered by the company. UC custodial workers nearby start at $15.52 an hour, and would jump to $18.25 an hour after two years.

Although Barrera said she makes $10 an hour, UC has paid Performance First about $20 an hour for a janitorial worker, according to contract documents.

Neither she nor her husband have health benefits. Her 6-year-old son uses Medi-Cal.

Other workers have made a career out of UC contract work, sometimes outlasting their employers.

Antonio Ruiz, 45, has worked as a parking attendant at UC Berkeley since 1994 for four separate private parking companies. He makes $11.50 an hour taking tickets and shuttling cars, and supplements his pay by doing custodial work at a hotel. The typical day lasts from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m.

He blames the long hours for a recent separation from his wife. “I don’t have time for family,” he said.

Maria Carmen Sandoval was in a similar situation, working for a series of custodial contractors at UC Irvine from 1997 until 2012. Beginning in 2009, she and about 100 other workers insisted on equal pay after working for years alongside higher-paid UC employees.

In 2012, the university ended the contract and brought on 94 workers full time. Sandoval and her husband have had their pay jump from $10 to $16.49 an hour. They moved out of a four-bedroom Santa Ana home they were sharing with two other families, and into an apartment of their own with their three children.

Last year they went on their first-ever vacation, down the road to Disneyland.

“It’s something I couldn’t do before, but finally I’m able to do it,” she said. “Now I know I can count on my paycheck.”

[Source]: LA Times