The UC Regents’ Budget: the Trouble with the Prop 30 Norm

Since the passage of Proposition 30 prevented another 10% cut to state funding for the University of California, blocked similar cuts to CSU, and blocked still larger ones to the community colleges, the higher leadership guidance has been “curb your enthusiasm.”

The new head of the California Community College system, Brice Davis, said, “We are guardedly optimistic that we’re beginning to find a bottom here in California.” UC president Mark Yudof stated that the vote “put public higher education back on a pathway toward fiscal stability.” These are obviously not battle cries but expressions of relieved exhaustion. What does that look like, for UC?

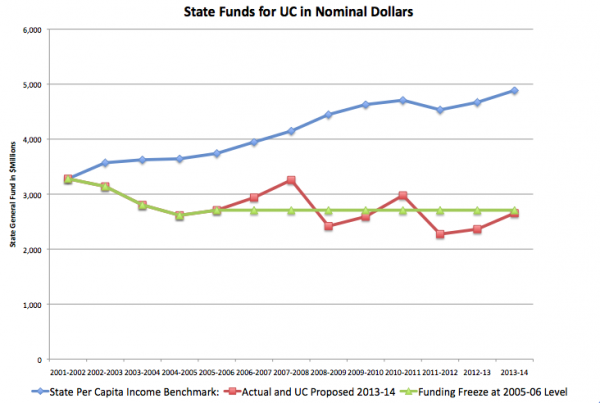

Here’s a simplified version of our traditional chart, since you love to see it as much as I love to update it:

As we know, investment in UC has long been falling behind growth in state per capita income. This is not a response to downturns but is an erratic yet secular trend of disinvestment. After years of turmoil, UC is slated to wind up next year exactly where it would have been had the state capped its share at 2005-06 and never increased this sum for enrollment growth or inflation. What we have had for years, and what we will continue to have with the Prop 30 track, is de facto privatization. It is privatization American style, will a hefty dose of public subsidy, but however much we don’t like to say it, that is what it is.

This won’t work, it sticks us with a new normal of assured mediocrity, its coping mechanisms will suppress new state investment, and it guarantees that students and faculty will gradually seek and find better venues than UC for that unique prerequisite to a non-plutocratic society that we call public higher ed. We now need to fight the Prop 30 norm as hard as we worked to install it.

First, in this post, let’s look at where the UCOP budget proposal puts us.

The UC budget proposal for 2013-14 will be discussed and assuredly passed as usual at the UC Regents’ November meeting, which starts tomorrow. The UCLA FA Blog has a good overview of and links to the major issues. The proposal is for a 6% increase in state funding, plus the equivalent of a 6% tuition increase that in a often-used ritual it asks the state to buy out. The one-page budget summary is the easiest way to get a quick take. Also see the helpful text of UCOP’s memo to the Regents’ Committee on Finance.

The current year general fund total is $2.378 billion, or about a billion below 2007-08, which we got to via around $2.1 billion in multiyear cuts minus some federal and other back-filling. To follow the devilish convolutions see paragraph two on page 3. For next year, the total new money is $150 million, plus $15 million for the new UC Riverside Medical School. Under Prop 30, the University gets this year’s tuition buy-out next year, so that figure shows up in the 2013-14 budget. This puts 2013-14’s proposed general fund at about $2.67 billion, including the tuition that we’re spending this year.

A few things to note.

1. Less new money goes to restoring education quality. $36 million is slated for campus restoration to instruction and research (expenditures list on p. 6), and another $25 million is targeted to deferred maintenance. The rest goes to the pension, health benefits, and routine salary increases. Because Regental policy suspended payments into the pension (UCRP) for 20 years, and because this holiday is done, any increase in state funding now comes with a hefty slice off the top before it goes to the campuses. This year, health and pension cost $95 million (for the state portion only), or nearly two-thirds of the total state fund increase.

2. “Efficiency savings” are a tragic bust. UC CFO Peter Taylor has repeatedly assured the Regents that $500 million could be saved in UC’s budget through umbrella campus contracts and various balance-sheet initiatives such as reinvesting some of the many billions of reserves held in short-term fund pools. During the worst of the crisis, he augmented the reputation of UCOP at the expense of the campuses, which he cast as foot-dragging opponents of efficiency and technology, thus reinforcing stereotypes of the wasteful public sector that have long hurt UC with the voters. Not long after the first floating of the $500 million savings goal, which implied $500 million of UC waste, Jerry Brown cut UC by $500 million. Now three budget cycles later, we have $20 million in savings on contracts and $20 million on reinvesting fund pools, and a possible $80 million through a debt restructuring that is opposed by UC unions and that has many long-term costs. What happened to the other $380-460 million in savings? They have not materialized, and meanwhile we have lost the funding that would have covered the expenses we actually incur doing instruction and research.

3. Fragmentation of the system continues. Differential tuition gaps are slated to increase with a new round of tuition hikes at professional schools. The latter has essentially taken UC’s premier professional schools away from the state, since state residents get no financial break for their tax support. In addition, Berkeley’s Haas business school wants to spin off its executive education program while promising to return net profits to Haas and to the campus. The Haas proposal is better than the Anderson School of Management’s — the problem with that was not becoming self-supporting but the phoniness of the self-support (see “How the Public Pays for Privatization”). Perhaps escape from direct Haas and UC supervision will allow it to increase cash flow back to those units by the factor of 4-5 that the proposal claims. The point is that now when a group of faculty want to do something really good, their default assumption is that UC isn’t good enough to serve as a platform for them. Unusual programs will increasingly follow the model of trying to leverage UC without being stuck in it.

4. Democrats’ default will cap one revenue stream without increasing the other. The 6+6 formula is likely to become the basis for the new Compact Framework agreement with the governor. 6% is at least twice the current rate of inflation,

and the tuition and debt bubbles have become national scandals that Barack Obama and every other Democrat will continue to rail against. There will be pressure to cut or eliminate tuition hikes, and yet their sheer possibility and repeated prior use give politicians an excuse to keep public funding flat.

To make any headway post-Prop 30, we have to very clear that Prop 30 itself, to quote Regent Bonnie Reiss,

will not prevent the “slow death of public higher education” (page 16). To the contrary, Prop 30 will lock it in. Most of the Regents know it, faculty know it, and President Yudof knows it. What are we going to do now with all this wonderful knowledge? Stay tuned.

[Source: Remaking the University]