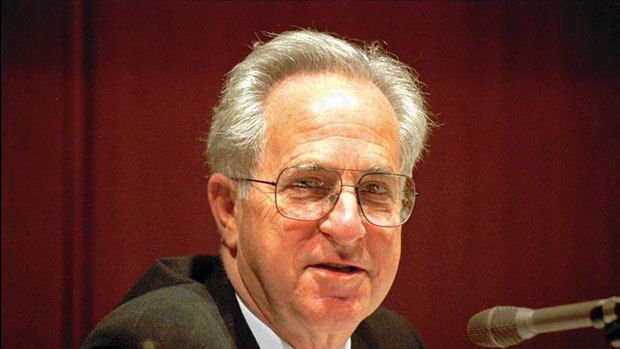

Jack Peltason dies at 91; former UC Irvine chancellor, head of UC system

By Steve Chawkins

Jack Peltason, a constitutional scholar with a modest manner and a homespun sense of humor who was a former chancellor of UC Irvine and president of the UC system for three years in the 1990s, has died. He was 91.

The cause of his death Saturday was Parkinson’s disease, UC Irvine officials said.

————

FOR THE RECORD:

Jack Peltason: In the March 23 California section, the obituary of Jack Peltason, a former chancellor of UC Irvine and former president of the UC system, said that he had five great-grandchildren. There are eight. —

————

Peltason signed on with UC Irvine even before the campus accepted its first students in 1965. As vice chancellor of academic affairs, he hired the university’s first faculty members and helped shape its initial academic offerings.

As UC Irvine’s chancellor from 1984 to 1992, he was credited with guiding the university through a hectic period of growth that included construction of more than three dozen major campus projects and recruitment of faculty superstars from other schools. Enrollment jumped 34% to nearly 17,000, and UC Irvine honed its reputation as a formidable research institution.

But Peltason sometimes was criticized for not being bold enough. Gay students slammed him over his refusal to provide campus housing for domestic partners, and some minority groups said he should have been more aggressive about building the ranks of African American and Latino students.

When he was appointed UC president in 1992, the bookish, genial Peltason was 69 — too old, his critics said, to provide effective university leadership.

With typically wry candor, he addressed the issue in his acceptance speech.

“There has been some concern about … a generation gap,” he said. “I think that concern is exaggerated. I do not have any trouble getting along with older people.”

“I serve at the pleasure of God, my wife and the Board of Regents, in that standing order,” he said at a news conference. “I will continue to serve as long as those three want me to.”

Peltason became head of the recession-stricken UC system as it was reeling from state funding cuts. Student fees increased by more than one-third. Faculty members went without cost-of-living increases for two years and then took a 3.5% pay cut.

Peltason managed the university through stormy economic times. In 1995, Gov. Pete Wilson proposed modest budget increases for higher education. Peltason, with his calming, conciliatory style, was credited with keeping the faculty’s confidence.

At the same time, he faced a bitter political fight as conservative university regents voted to abolish race-based preferences in student admissions, hiring and contracting.

Along with chancellors of the state’s nine UC campuses, Peltason futilely opposed the 1995 move.

“Our affirmative action and other diversity programs, more than any other single factor, have helped us prepare California for its future,” he wrote in a letter to the regents. “To abandon them now would be a grave mistake for the university and for California.”

Born Aug. 29, 1923, in St. Louis, Peltason received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Missouri. In 1947, he received his doctorate in political science from Princeton.

In 1952, he co-wrote “Government by the People,” a book that, along with his “Understanding the Constitution,” became a standard text in political science classes. Both were issued numerous times in revised editions.

“I don’t play golf,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1992. “I work on one of my textbooks every day. That’s my therapy.”

Peltason taught at Smith College in Northampton, Mass., before teaching at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he served as dean of the college of liberal arts and sciences from 1960 to 1964. After three years at Irvine, he returned to Illinois, where he was chancellor until 1977.

With local officials, Peltason summoned the National Guard to campus twice during Vietnam protests. He received death threats; at one point, a caller told his wife, Suzanne, that their son Timothy had been critically injured in a car wreck. After three anguished hours, the Peltasons learned that the call was a hoax.

In 1977, Peltason became president of the influential American Council on Education in Washington, D.C. While there, he championed the notion that college students meet certain academic standards before participating in sports.

“It took guts to push that idea because a lot of colleges did not support it,” the Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, a former president of Notre Dame, told the Orange County Register in 1987.

In Irvine, Peltason was credited with easing strained town-gown relations.

In a 1992 interview, Irvine Mayor Sally Anne Sheridan said Peltason once was invited to a black-tie arts reception at a local park but apparently didn’t know it was a formal affair. He showed up that night in a jumpsuit, carrying a flashlight.

“It didn’t bother him at all that everybody was in evening clothes,” Sheridan recalled. “He has a grand sense of humor about himself. That endeared him to everybody.”

Peltason’s survivors include Suzanne, his wife of 68 years; children Nancy, Timothy and Jill; seven grandchildren; and five great-grandchildren.

[Source]: LA Times