Are Women the New Face of Organized Labor?

By Anna Louie Sussman

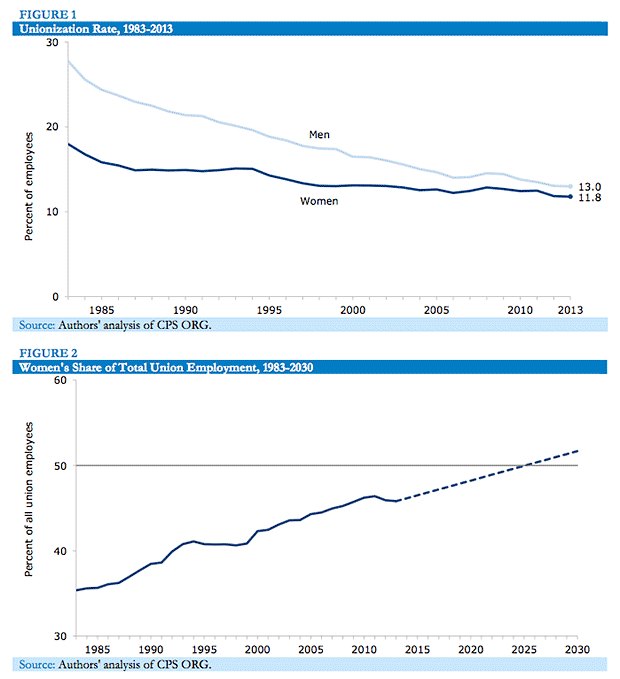

Unionized labor represents an ever-smaller share of the American workforce, having fallen to 11.1% in 2014, down from 20.1% in 1983, according the U.S. Labor Department. But as men’s union membership fallen steeply, women, and particularly women of color, have been the majority of new organized workers. Their presence could shift labor’s agenda.

The growing female union presence dates back at least to the 1980s, when many public sector jobs became unionized, said Kate Bronfenbrenner, the director of labor education research at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations. One 2014 study by the left-leaning Center for Economic and Policy Research forecast that women will be the majority of unionized workers by 2025.

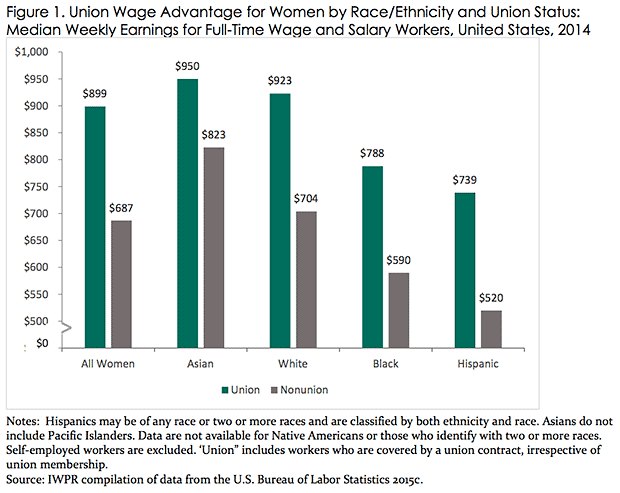

Union membership goes a long way toward closing the gender pay gap: A new analysis by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research shows that women in unions have median weekly earnings 31% higher, on average, than nonunion workers. Even controlling for other factors that influence wages, such as education and age, women in unions still have a 13% “union advantage” over their nonunion counterparts in the same jobs, which translates to around $2.50 per hour, the 2014 study by CEPR found.

There’s evidence that women’s increasing prominence in unions is already influencing what workers demand at the bargaining table. Ms. Bronfenbrenner, who has reviewed the content of union contracts from the 1980s and 1990s, said antidiscrimination clauses are now appearing in contracts more frequently than in earlier decades. She is also seeing contract provisions on issues like scheduling and sick days that disproportionately affect women, who still do the majority of care work, although it is too early in the research process to tell whether their prevalence has increased from earlier periods.

A recent ruling has the potential to accelerate this historical trend. Last month, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that unions representing subcontracted employees could potentially bargain with the lead firm, by expanding the definition of what constitutes a “joint employer.”

Many labor experts believe that franchises such as McDonald’s, which is currently in litigation with the labor board, could be next. If fast-food workers and other franchise employees are more easily able to bring the parent company to the bargaining table, it could raise women’s profile, potentially changing organized labor’s agenda.

Wilma Liebman, a former member of the NLRB, said the ruling came in response to changes in the economy that appeared to be creating a lot more low-wage work, which disproportionately affects women and minorities. Women make up two-thirds of the low-wage workforce (defined as making $10.10 per hour or less), according to the National Women’s Law Center, and few of them are currently unionized.

Businesses groups said the ruling would disadvantage self-employed subcontractors, who would now find it harder to get jobs.

“If this decision stands, the economic rationale for hiring a subcontractor vanishes,” said Beth Milito, senior legal counsel for the National Federation of Independent Business, following last month’s ruling.

John Schmitt, one of the authors of the CEPR report and now research director at left-leaning think tank Equitable Growth, suggested that as women became more numerous–and powerful–within unions, labor’s agenda would evolve.

“As women approach 50% of the labor movement and, over time, become local union presidents and national officers and then presidents of national unions, I do think that the opportunity for issues that are traditionally women’s responsibilities will be pushed further and further to the center,” he said.

To be sure, just because a workplace is now allowed to bargain with the parent company, it doesn’t mean it will. Ms. Liebman said the “joint employer” status is made on a highly factual, case-by-case basis. And Mr. Schmitt noted that workers at Walmart, a single employer, have had tremendous difficulty organizing even before this ruling.

[Source]: Wall Street Journal